The Chosun, the oldest and largest newspaper in South Korea recently published an article about Lithuania’s cutting-edge laser technology. Korea associates our country’s success in the laser industry with companies such as Akoneer that drive innovation by actively collaborating with academia to develop new technology.

Lithuania is the Unrivaled Leader in Laser Manufacturing

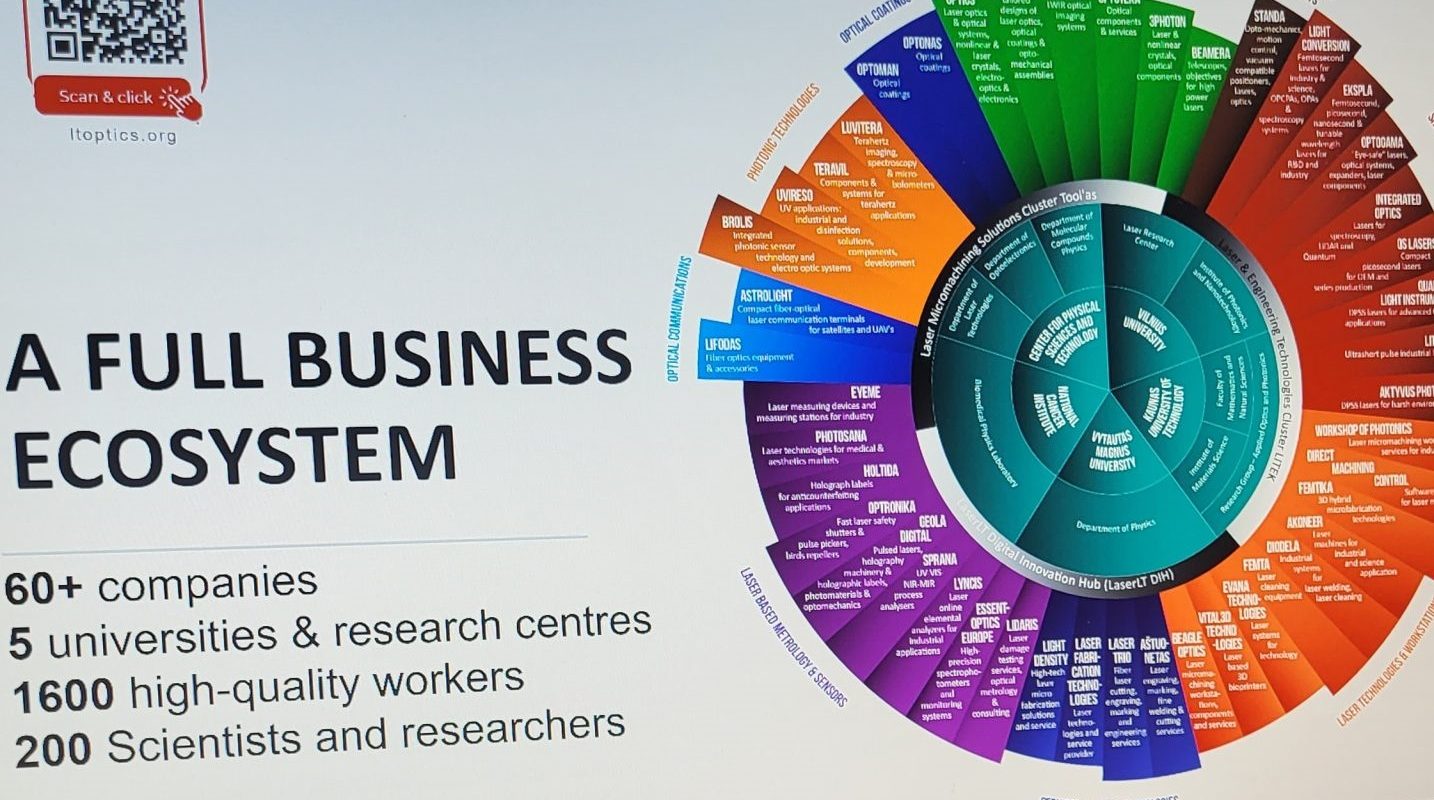

Lithuania was described as a small Baltic country with a population of 2.7 million. Despite its size, the country is unrivaled globally within the laser industry. There are around 60 companies that are exporting laser devices and related technologies to leading companies and research institutes and to over 80 countries around the world. Lithuania’s laser industry, with an independent ecosystem, remains unaffected by external threats, as explained by Lithuanian Laser Association (LLA) President Gediminas Račiukaitis in the article.

From Developing Cutting-Edge Technology to Winning Prestigious Awards

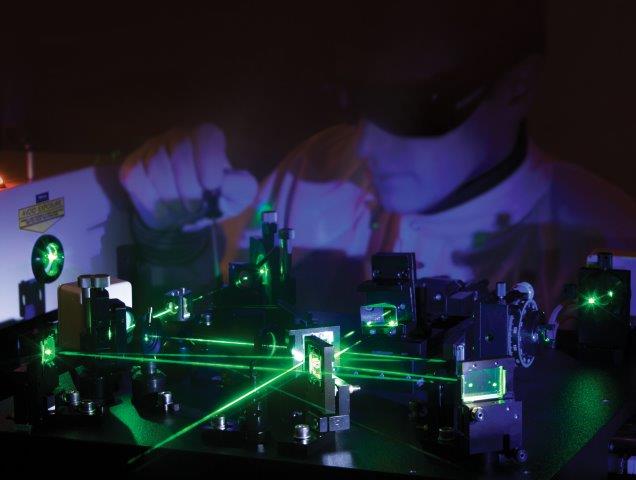

Lasers, at their core, work by producing the power of a nuclear power plant in a small space and an extremely short period of time, are considered an essential element in today’s high-tech industries. Laser micromachining is effective in precisely processing various materials. For instance, hundreds of thousands of semiconductor and glass components that go into smartphones or TV displays are all cut with lasers.

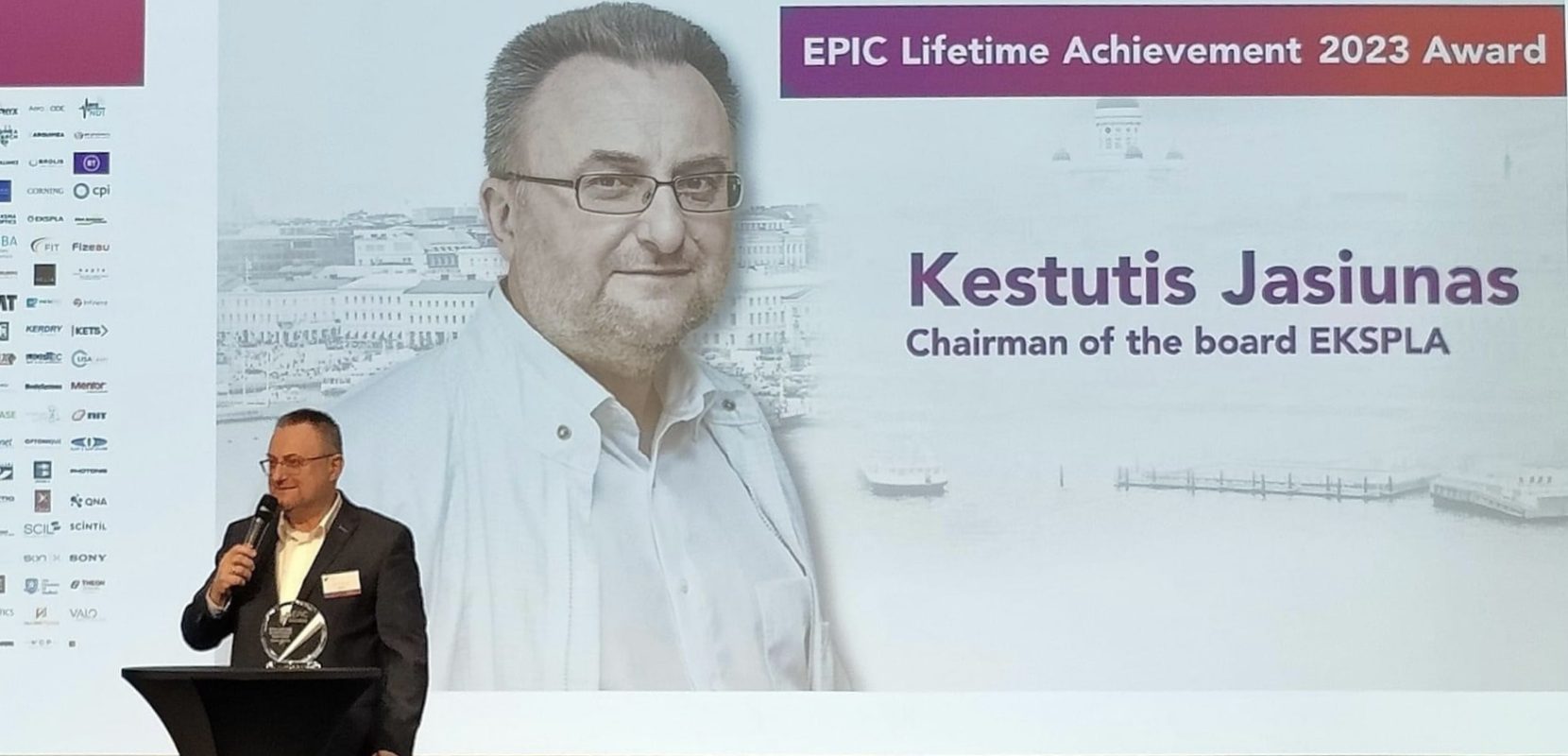

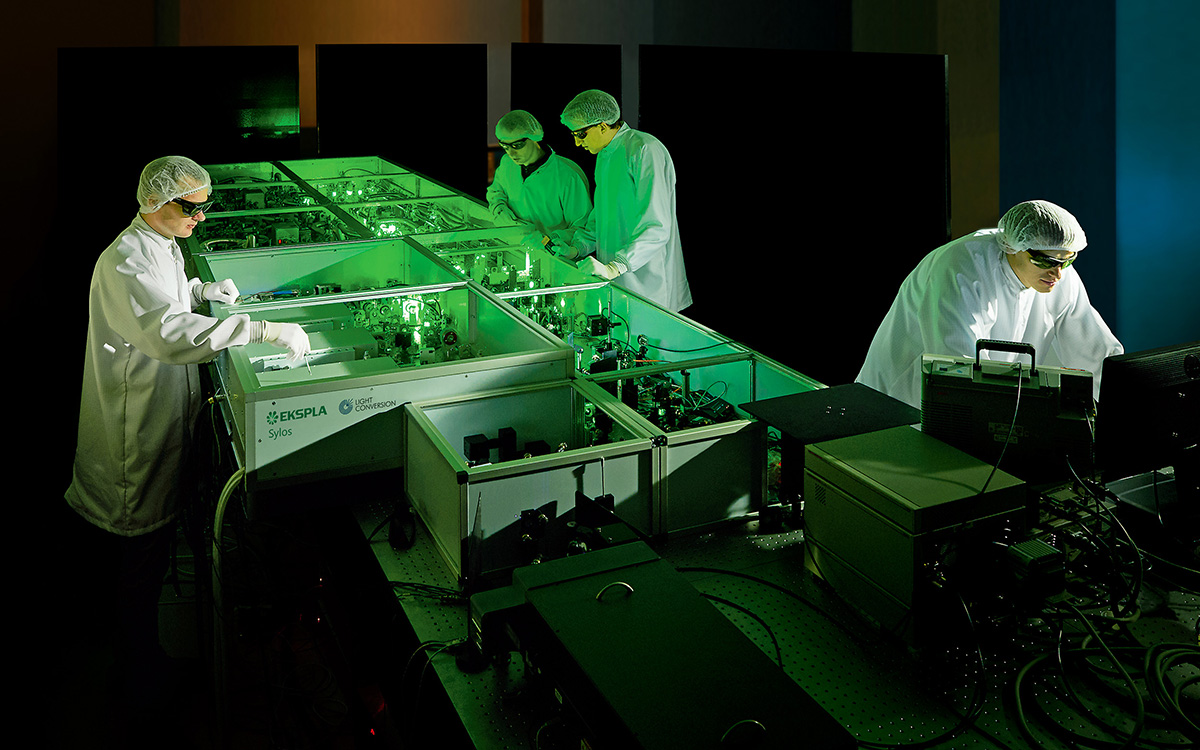

The Chosun acknowledged that Lithuanian company EKSPLA won the Oscar of the laser industry, the prestigious International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE) Prism Award, for the best laser – the FemtoLux 30. The SPIE Prism Awards are held during the Photonics West (USA) conference and exhibition. EKSPLA Chairman Kęstutis Jasiūnas explained that ‘if the 21st century was the era of electrons, the 22nd century will be the era of photons (which make up lasers).’

Akoneer Drives Innovation through Industry-Academia Cooperation

Lithuania’s competitiveness in laser technology was associated with active industry-academia cooperation. Lithuania’s first laser was fired in 1966 – merely six years after the world’s first laser in the US. The first Lithuanian laser was used to research semiconductors. Since then, laser laboratories have been established at the Institute of Physics and at Vilnius University. Currently, there are five laser research universities and institutes in Lithuania, and about 200 scientists and 1,800 professionals are working in the laser industry.

Companies also actively acquire the latest research from academia. Akoneer, a Lithuanian company specializing in laser micromachining systems for industrial and scientific applications, serves as an example of such collaboration in the article. Company’s CEO Rokas Šlekys was quoted, explaining that Akoneer’s CTO is working part-time at a research institute and is responsible for developing new technology. ‘We often collaborate with academia for this purpose’, he said. In 2022, the company introduced laser machines for Selective Surface Activation Induced by Laser (SSAIL) technology that enables conductive traces to be formed on many standard dielectric materials.

„Akoneer“ lazerinio mikroapdirbimo sistema

Lithuania’s Milestone with Taiwan and Strengthening Cooperation with Korea

For the first time in 18 years in Europe, a Taiwanese representative office has been established in Lithuania. Taiwan is home to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest semiconductor consignment production company, and the two countries are accelerating cooperation by opening the Lithuanian Laser Laboratory in Taiwan in September of last year.

Lithuania’s next step is to strengthen cooperation with Korea. LLA President Gediminas Račiukaitis said that the conditions for exchange between the two countries have improved, such as the establishment of the Korean Embassy in Vilnius this year. In July of last year, President Yoon Suk Yeol visited Lithuania, the first Korean president to do so. The leaders of the two countries promised to expand cooperation in the high-tech industry, including the laser field, and to open the Korean Embassy in Lithuania. Korea and Lithuania established diplomatic relations in 1991 and are celebrating their 33rd anniversary this year.